Revisionist Westerns have blurred the line dividing good and evil people in the “Wild West” since their appearance in the late ’60s. The classic fight against criminals and rogues has been undertaken by do-gooders with varying levels of moral ambiguity. The term ‘revision’ makes you think that the filmmakers are changing history, that there is a deviation from what is accurate to the times and, therefore, the story. But to revise the conventional Western film is to break from a white-washed, ‘safe’ rendition for the average audience. Whether the 70’s anti-Westerns from Leone and Peckinpah or the more recent neo-Westerns from the Coen Brothers and Mangold, a contemporary depiction of a lawless Old America allows for a modern commentary on the themes and traditions of a morally-complex period.

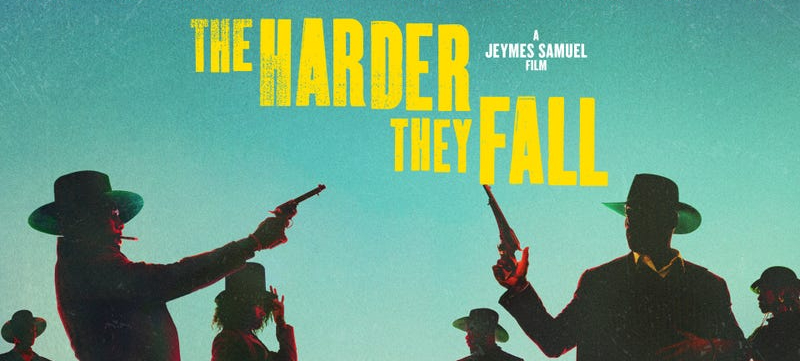

Directed by first-timer Jeymes Samuel, The Harder They Fall broadens the revisionist concept to new heights. Samuel gives us something we didn’t even know we wanted: a pop-action Western with an ensemble of actors and actresses portraying mixed-race and African-American gunfighters, outlaws, and lawmen. Fear not! Its representation is done not in the vein of the Blaxploitation Westerns that came before but with respect and power instilled in its Black characters.

Though it boasts an uncompromising style and technique, the film loses itself in its extravagance at times. It dawdles in its pacing after a certain point, making me wonder when we’re finally gonna get to where I know we’re going to go. And while its analysis of a vengeance-fueled, cycle of violence is welcome, the commentary isn’t as strong as it thinks it is. Nevertheless, this is a movie that knows what it is and wants you to know it too. The design of this world, combined with amazing acting and a magnetic soundtrack to match, is one I want to see more of; it’s the type of film I think can be built on and evolve in the years to come.

The film follows Nat Love (Jonathan Majors), a gang-leading outlaw who robs other robbers, as he seeks revenge against his nemesis, the ruthless Rufus Buck (Idris Elba). Joining him in the Nat Love gang are the quick-draw prince Jim Beckwourth (RJ Cyler), sharpshooter Bill Pickett (Edi Gathegi), and lover-turned-saloon owner Stagecoach Mary (Zazie Beets). Working with U.S. Marshal Bass Reeves (Delroy Lindo), Love goes after Buck and his compatriots – the legendary Cherokee Bill (Lakeith Stanfield) and brutal Trudy Smith (Regina King) – as the recently pardoned criminals attempt to build up their Black utopian town in the Western territories.

Revenge is a common motivator for the plot in most films, driving the protagonist towards an enemy that he has a personal vendetta with. Westerns, moreso than any other genre, are built on the protagonist/antagonist relationship; this association lives or dies on what it means for each of these characters to see the other fall. Showcasing the payback-based plot in a way that is not boring or overdone in other movies is part of what makes an audience interested in seeing this revenge through.

We first meet Nat Love in our opening scene as a young boy about to enjoy a meal with his loving parents. It’s like any ordinary dinner for them until Rufus Buck (unseen at this point) comes-a knocking on their door. Elba says nothing as he saunters inside, but Love’s father knows precisely what Buck is looking to do. He begs and pleads for the forgiveness of some sort of wrongdoing against the man but can only watch as his wife is shot, following her shortly after. To finalize his action against the Love family, Buck has a gang member hold down young Nat as he carves a cross into Love’s forehead, Aldo Raine-style.

It’s brutal, it’s tragic, it’s the setup this movie needs. Starting with a heart-wrenching family assassination tells us exactly what this movie will be about and how deep the connection between Love and Buck goes.

The film’s strongest point is its actors, bringing these characters to life and matching the pizzazz the director put into the film’s design. Majors personifies the tragic hero of Nat Love as someone who just got a wrong lot in life. Love has a moralistic disposition, but his past actions following his parents’ murder make being a “good guy” impossible for him. Majors gives off similar Western-leading man vibes that John Wayne gave in Stagecoach; his charming swagger, walking through the film’s landscapes like it was built for him, makes the idea of Major appearing in more Westerns an enticing one.

Elba’s presence as a villain has us afraid of him before we even see his face. After being freed from imprisonment by his gang, his first breath as a liberated man “shifts” the world around him, adding to the gravitas and power he emanates. When he comes to take back control of the town he built from former partner and double-crosser Wiley Escoe (Deon Cole, a surprising scene-stealer), Buck shows how he believes he’s in the right and has no qualms about killing for his perceived “good intentions.” We’ve seen it before, but the context of creating a Black utopia paints a different argument for whether we even want to see Buck fail.

Though Beetz’s performance as Mary was enjoyable, the character’s constant teetering between love interest and kick-assery detriment her just enough. Despite her introduction as a no-nonsense, independent, quasi-co-leader in the Nat Love gang who can handle her own, but is quickly put in the damsel-in-distress role when the plot calls for it, giving motivation to Love to follow Buck’s instructions. While Mary does come out in the end as a sort-of empowered damsel, going against Trudy in a brutal fight, Beetz just doesn’t return or come close to who her character was in the beginning.

Regina King’s villainess Trudy Smith is a true equal to Buck. No romance between these partners except love for their constructed city, a relationship built on respect (and possible fear of what the other is capable of). They are strong together, but King holds her own separate from Elba; her motivations and persona seem driven by her psychotic nature, and sticking by Buck seems to tame that streak temporarily. But that brutal side of Trudy lets King be the film’s badass in her own right, giving it her all not just in action, but in the tense scene between her and a captive Mary.

Stanfield’s Cherokee Bill isn’t given nearly enough material, but I suppose that adds to his ominous dispostion. Bill is played like a haunted folk hero, where the line is blurred between man and legend. He’s philosophical, but defiant of the tales told about him; knowing any truths about him would only shatter his image.

While the film was a great showcase of beautiful art direction (look at these costumes and sets!) and Black actors shining like never before, the message it was trying to speak from the beginning falls flat when realized by the end. Knowing when he’s been beaten, Buck illuminates Love on his motivation for killing his family all those years ago: the two are actually half-brothers through their father. The latter abandoned Buck as a child after killing his wife. Turning Love into the same kind of person Buck turned out to be was “his final revenge” against his father. That’s great! I wish that were revealed and hanging over our heads about 20 minutes earlier instead of dropped out of nowhere in the second-to-last scene.

Pacing is the biggest thing going against this film. After all the introductory scenes, meeting all the players in this game, we stagnate for a bit. It feels like the movies just cycling through the scenes, rather than letting those scenes serve their moment. Even the bank robbery scene didn’t have the energy or “pulse” that was consistent in the other tense/thrilling segments. Brought me out of the movie for a bit, which I hate to say because of all the other remarkable aspects of the film.

Saving the best for last: THE MUSIC!! Goddamn, if this wasn’t the most praise-worthy soundtrack for 2021. The score is anachronistic by design, giving that modern punch it deserves for its modern perspective of the Old West. Samuels’ hip-hop infused arrangements do for this film what Ennio Morricone’s brass-y trumpet/orchestral pieces did for Spaghetti Westerns. It just works! It’s fun to listen to, masterfully fitting each action scene through its slow-motion or bullet perspective. The track “Three And Thirty Years”, in particular, pays homage to that operatic quality in certain songs by Morricone for Leone’s Dollars Trilogy. When you hear it in the first scene as Buck kills Love’s parents, its a moving piece that almost guides you to empathy for the character’s loss.

The Harder They Fall has the style and boldness I wish all mid-budget movies had nowadays. It relishes its idealized Western world, featuring real-life outlaws and gunslingers in a dramatic pretense you wish actually occured. Jeymes Samuel has an eye for the modern movie people want to see. Its a shame the release was limited and didn’t go far beyond Netflix. In a perfect world, this would’ve dominated theaters and the home video market for weeks. Let’s not make it a wasted effort and go watch the movie!