Much like the Maysles Brothers, whose “direct cinema” style painted virtually unprompted portraits of the Beales of Grey Gardens, directing duo Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky weave a unique, cinematic true-crime story by ingratiating themselves with Delbert Ward, a simple-minded farmer accused of murdering his brother.

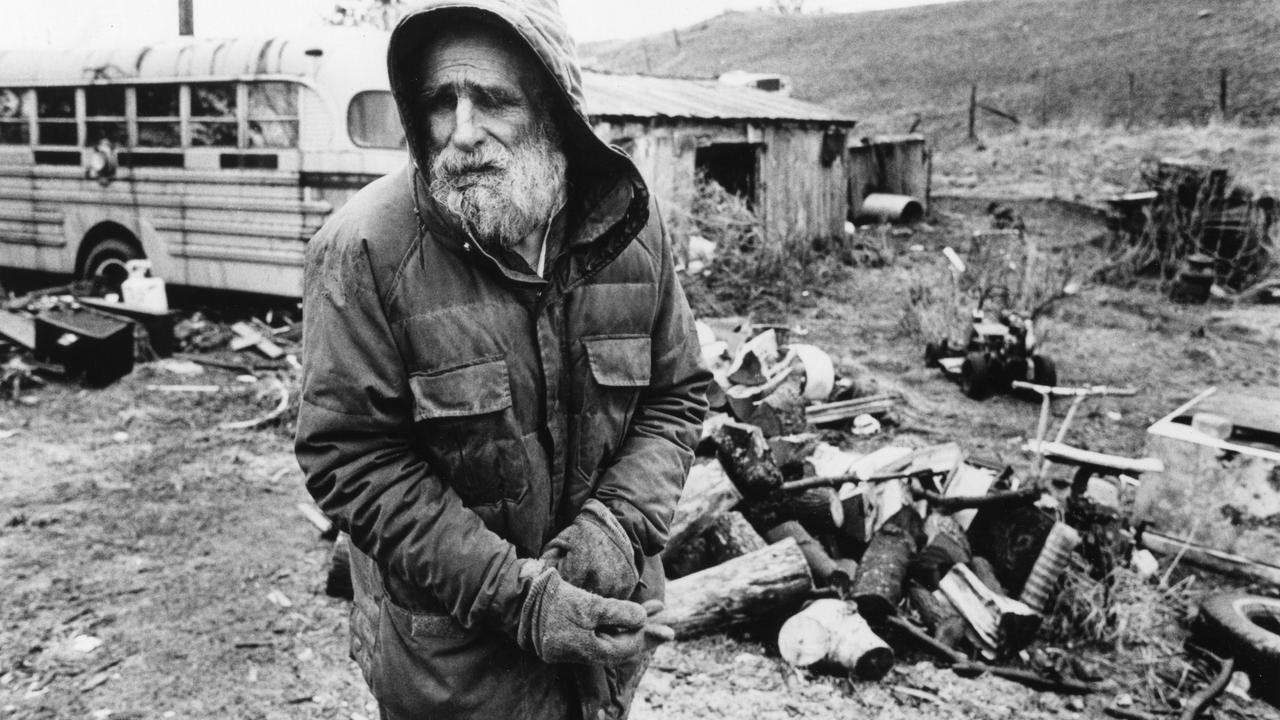

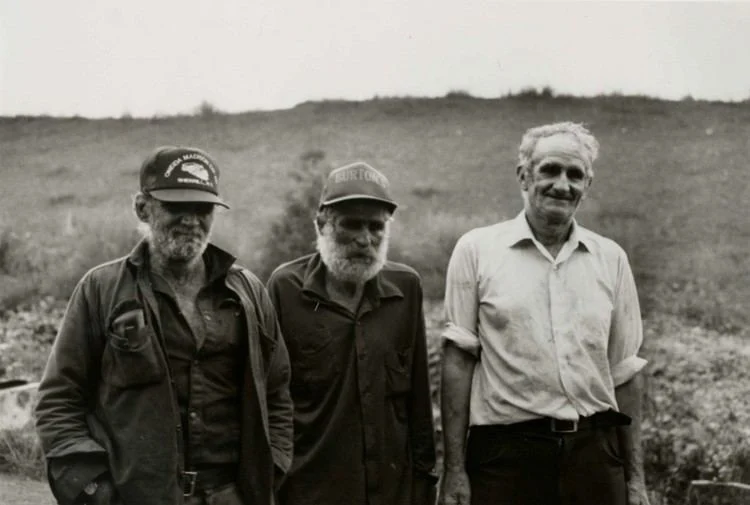

Considered by the locals of Munnsville, New York, to be eccentric but friendly, the Ward Boys (as they were collectively referred to) lived in a decrepit shack together their whole lives. Sharing their beds for warmth in the unheated hovel, Roscoe, Lyman, William, and Delbert were uneducated, anti-social farmers who were content toiling on their familial land for the rest of their lives.

This untroubled existence was thrown into disarray when on June 6th, 1990, William was found dead in bed. The man was 64 and had been in poor health for some time. It seemed like natural causes until the coroner determined that William had been suffocated. Police interrogate the family, and Delbert confesses to committing the act, calling it a mercy kill for his ailing brother. He signs his confession and is placed under arrest. Movie over, right?

If only it were so cut and dry.

The brothers and the neighbors claim Delbert was coerced into confessing due to his dim-witted nature. A plausible argument is made that Delbert doesn’t fully understand the legal process and the questions the police were asking him. One constant supporter spoke bluntly about the accused’s mental capabilities, “when they asked Delbert if he was ready to waive his rights, he didn’t know the difference between that and waving to someone on the road.”

What’s so interesting is the filmmakers’ seamless integration into the village. The filmmakers got to know these people and became familiar with them to the point where having the camera pointed at them wasn’t a concern. As I stated before: when the Maysles did it with Grey Gardens, they captured spontaneous moments that presented the true personality of their subjects. Documentaries always seem constructed, a facade due to the camera’s presence. But to have these timid men, who always kept to the edge of society, invite the filmmakers into their home and be comfortable (though you could argue more naivety than a trust) to talk honestly is a fantastic feat.

This close proximity musters the question of exploitation, of course. Should the lives of these men, strange as they may be, be used as entertainment? Should we peek behind this curtain into the lives of clearly disturbed and abnormal individuals to capture a story? The Ward Brothers are unassuming enough not to see an issue with it, but their “caretaker” neighbors know better. However, they practically invite the documentarians’ presence, firm in their conviction of Delbert’s innocence/case. Even the defense lawyer is happy they’ve captured the events as it could help Delbert’s image as the prosecution slanders it.

The news media circuit that swarms the town didn’t seem to exercise that same cordial form of caution while the documentary was filming. It’s a stark contrast: Berlinger and Sinofsky gradually make their presence a regular sight by conversing honestly with the townspeople; The reporters seem like foreign invaders who insert themselves haphazardly and falsely. When one reporter films in the dance hall, you can see the way people stare at her and seem to find her presence awkward.

Something the film does interestingly is not explicitly swaying the viewer to a certain truth surrounding Delbert’s innocence. Sure, they find Delbert innocent, and he’s free to go. But everyone is left to their own devices on what happened throughout. During a dinner early on in the movie, a group of neighbors debates the implausibility of Delbert suffocating his brother. Another says that if he had done it, it’s because Delbert thinks of life and death differently within his farm-wired brain. Delbert might’ve done the same for William the same way you’d put down an injured animal. But no matter how you feel about mercy killing, entertaining the theory harms the case, so it was wise of the defense to ignore this—focusing on the prosecution’s lack of physical evidence.

We all know some weirdos: Former classmates who acted strangely. Neighbors that rarely came out of the house. That random guy who walks down the street mumbling to himself. They’re the untouchables, people your parents told you to stay clear of. Besides the elements of true crime, the documentary preaches a more personable message. Here are three outcasts, usually never given the time of day by the town patrons. Suddenly, those who ignored them step up and offer assistance in their time of need. It’s the sentiment of, “Yeah, they’re weirdos. But dammit, they’re our weirdos!” that attracts me.

It invokes a feeling of human compassion. You learn to feel for these guys as you witness their plight, seeing firsthand the lengths of their separation from modern society. Watch the scene where a news reporter speaks on what neighbors say about the Ward Brothers behind their backs, not in a mean-spirited way, but in an honest way on the boys’ issues and mental capacity. Delbert, Roscoe, and Lyman all watch this on their crummy television, and you can see that they don’t fully understand the meaning behind the words. They can’t take offense because they don’t even know they’re being offended.

There’s an element of authenticity behind this film that divides you on whether Delbert should be found guilty. We follow the brothers and their acquaintances, but the talks with police that directly parallel discussions of the case are just as crucial to informing you. It’s this context that you wish was available in certain legal issues, a context that tells the true character of an accused. The context you are given, these guys’ lives in squalor, and through interactions with kindly associates, sends a different message through your brain. You can see no falsehoods, nothing fake about what Berlinger and Sinofsky present.

Equal parts a true-crime documentary and a rendering of the endurance of rural society and its people, this is a film meant to make you feel something while delving into a terrible case of legal inequity. Love for thy neighbor, minder of those needing assistance…Brother’s Keeper is a heartwarming film about justice for the subdued, something for times like now when the modern legal system still operates like this today.