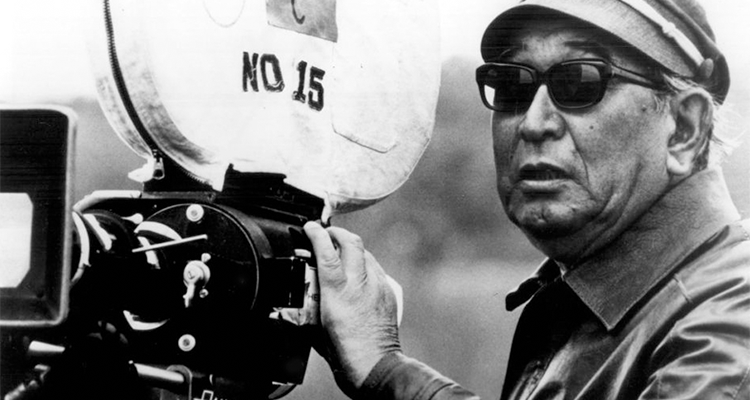

Renowned Japanese director Akira Kurosawa is a master of letting his personal views shape his work without allowing them to dilute the end result into a self-righteous mess. Across 30 films, his values shaped the best of them with remarkable consistency.

With Drunken Angel (1948), Kurosawa took a quiet stand against the US occupation of Japan, using yakuza drama to further his allegory. Stray Dog (1949) framed the Japanese people’s post-war identity in a noir police procedural context. His filmography is abundant with social messages, heightened by engaging stories and gripping characters. Many directors can say the same, but not many can display their core tenets overtly yet with respect and grace, as in the case of Kurosawa’s 1990 film, Dreams.

I found Dreams, a magical realist outlier compared to all of the filmmaker’s historical epics and contemporary dramas, to be a slept-on culmination of his commentaries. The movie comprises eight segments; anthological stories much like how you can have multiple dreams in one night’s sleep.

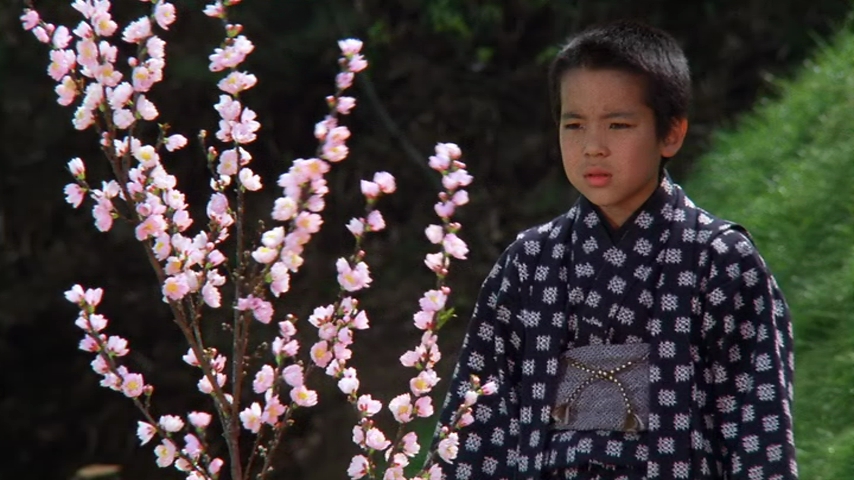

The singular constant is our protagonist, “I” (aka The Dreamer), who serves as a proxy for the director as they roam through these vignettes. Appearing as both a little boy (Mitsunori Isaki & Toshihiko Nakano) and a grown man (Akira Terao), The Dreamer morphs like a chameleon, changing his face and person along this shifting dream environment while bringing the audience closer to the popular filmmaker.

The exceptionality of his vision comes from how he approached it; for Kurosawa, Dreams is the closest he can get to creating a painting, an artform he had a life-long passion for but could never make a living from in his early years. The vivid color palette and art direction to create a world of both bright beauty and dingey nightmare are enough to brand itself in your eyes as picture-perfect.

While they may have an air of austere simplicity, his messages don’t fail to sway you anyway. Not every film has to challenge you to discover its thematic intention; some prosper from a straightforward display. Kurosawa abandons any constraints that a narrative would impose, allowing the images and overt exploration of human nature, nuclear concern, and environmentalism to take precedence.

We start with “Sunshine Through the Rain,” where a young ‘I’ ignores his mother’s warnings, finding himself a forbidden witness of a kitsune wedding procession. From behind a tree, he watches the anthropomorphic foxes creep slowly, tiptoeing and swiftly turning their heads almost like a dance to ensure no one is watching them. Once the anthropomorphized creatures spot him, ‘I’ tries to return home, only to be told that he must take his own life for the transgression. The child Dreamer, no more than six at this point, is sent away, seppuku blade in hand, searching for leniency from the creatures he offended.

The Dreamer moves on to “The Peach Orchard,” where he faces anger from the spirits of the peach trees his family chopped down. The Dreamer pleads for the apparitions, appearing as traditional figurines used to celebrate Hinamatsuri or Doll’s Day, to understand that he cherished the orchard; that he shed tears when they razed it because he appreciated their beauty so much. Recognizing his truth, the spirits permit ‘I’ to see the blossoms once more as they dance to the most captivating music, allowing a temporary vision of the once-thriving grove.

“The Blizzard” finds the Dreamer leading a team of mountain climbers in the middle of a harsh blizzard, strained and lost amidst the blinding snowfall. One by one, the others slump over, accepting their fate of being lost on the cliffside. Even the Dreamer is seduced to a frozen death, lured by a Yuki-onna (a demon snowlady), but he breaks free and awakens the others, rejoicing that the now-dwindling storm revealed their camp a few feet away. It’s a clever distortion of Kurosawa’s love for hiking; the feelings of despair and accepting death over further anguish and hardships understandably make up any climber’s worst nightmare.

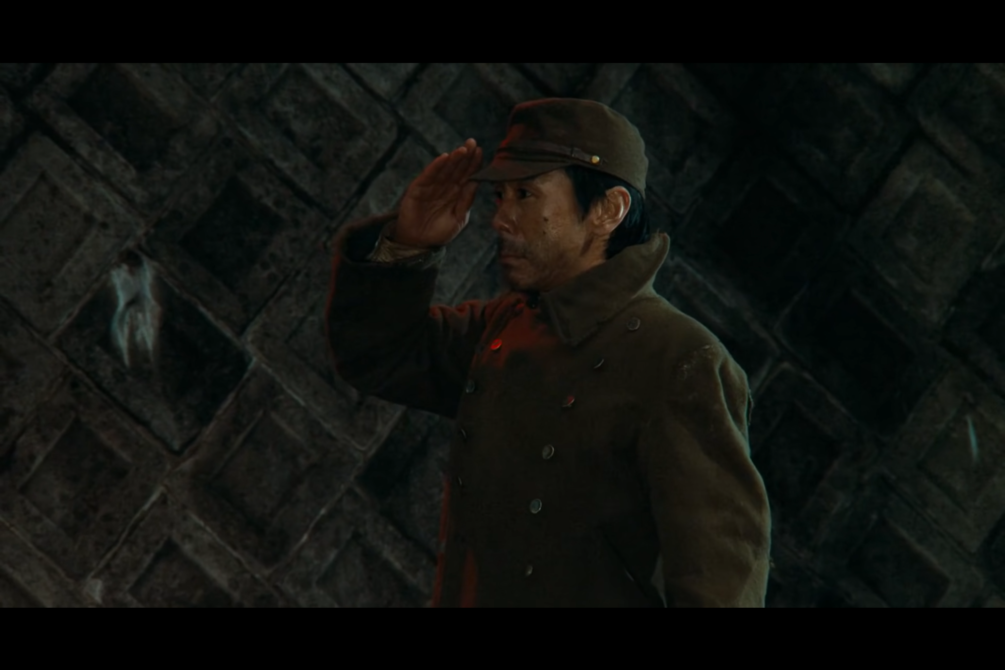

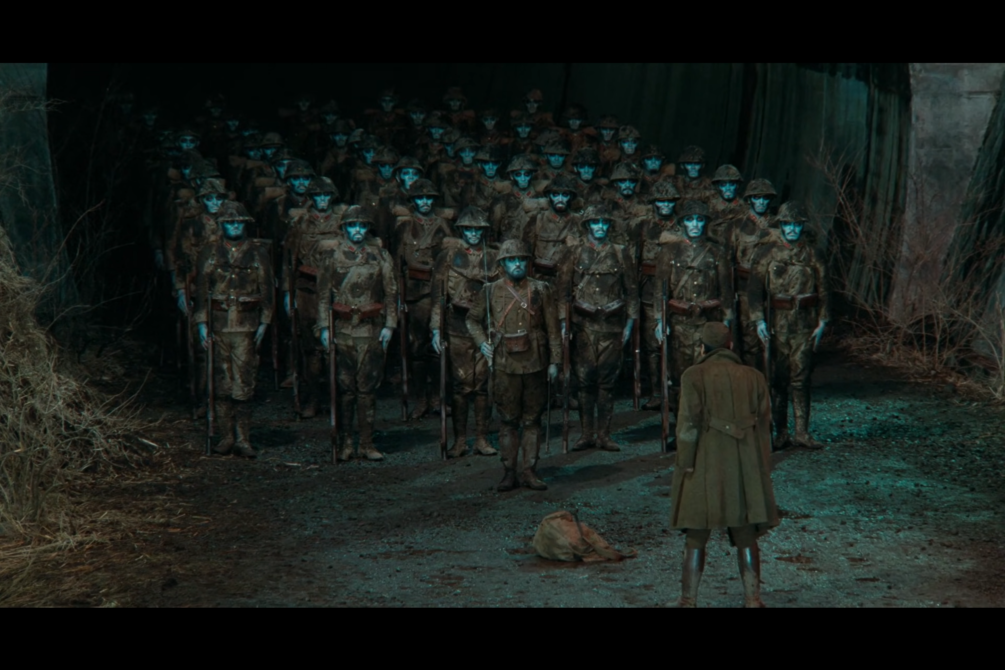

We take another drastic turn into nightmare land with “The Tunnel.” The Dreamer has transformed into a discharged army commander, traveling through a shadowy tunnel when he suddenly finds that a ghastly, deceased soldier has followed him to the other side. He struggles to maintain his composure, insisting to the young man that he died in his arms after a battle.

Just as he sends the trooper back through the tunnel, his former unit, all killed in action, walks out in march step. The sight of the sullen, blue-faced army unsettles the former leader, but not as much as agonizingly informing them through shameful tears that “the Third Platoon was annihilated” due to his misconduct, and he alone survived. The legion is unmoved until he gives them a final order to return to the land of the dead, back through the ominous dark of the passageway.

The most iconic of all the shorts is the one featuring Martin Scorsese as painter Vincent van Gogh, “Crows.” Jumping into a museum-framed painting of The Langlois Bridge at Arles with Women Washing (1888), ‘I’ finds the troubled artist and asks for artistic wisdom. Van Gogh, however, doesn’t have the time or the interest to answer any of the Dreamer’s questions, only focusing on the painting at hand. As he winds down and the world around him changes into the van Gogh iconic oil on canvas texture, the Dreamer seems to come to an understanding of his own artistic aspirations.

“Mount Fuji in Red” is, in all honesty, the most overt and blatant of all the segments; but when it comes to this film and its intent, that’s the best form it can take. I mean there’s nothing to mask it as a knock against the use of nuclear energy in Japan. In a country whose experiences with the worst of atomic power are unrivaled and unforgotten, all subtlety is out the window as the known dangers of this energy are realized tenfold.

The Dreamer arrives on the scene as people flee in terror after six nuclear reactors all go critical and explode. On a cliffside, the only remaining people are the Dreamer, a mother with two children, and a repentant man who reveals himself as the owner of one of the nuclear facilities. Faced with nowhere to go but the bottom of the ocean, the Dreamer tries to save them from the oncoming radioactive gases, but as the group is overcome and the screen fades to black, we understand just how unfruitful this’ll be.

With a similar air of obviousness but its message well-wrapped in a vigorous back-and-forth, “The Weeping Demon” is an utterly abysmal night terror, culminating Kurosawa’s fears for mankind’s future. This holocaust has damaged the natural ecosystem, and radiation has turned humanity into horned demons of Japanese myth. The seemingly untouched and out-of-place Dreamer walks the landscape and comes upon a mutant; it seems like this is the aftermath of the previous vignette, with the high-standing officials and upper class now suffering eternal pain for their greed and crimes against the natural order.

As the deformed human hunts him, we transition into the final vignette, “Village of the Watermills.” A tranquil ending, the bright green town is a precise antithesis to all the blatant environmental abuse we previously witnessed. The Dreamer speaks to a village elder (Chishū Ryū), and he learns about their harmonious, simple lifestyle in conjunction with nature. An ongoing funeral, which is more a celebration of life rather than mourning, further shows how creating a world of peace where people can live in serenity is the best outcome humanity can strive for.

One of the worst things a filmmaker could do is be self-indulgent, twisting the form of motion pictures to be “preachy.” You know it when you see/hear it; it’s a tone of vanity, an air of superiority that what you have put to celluloid is the only correct view. That aura does not exist in Dreams.

Calling it a soapbox for Kurosawa’s ethical imagination is a false representation of the director. This isn’t some young hopeful looking for praise and awards for his (what we’d now call out as “virtue-signaling”) positions. This man held many burdens, from witnessing the Kantō Massacre to the death of his brother by suicide and an attempt on his own life via self-harm after an endeavor into big-time Hollywood sullied his viability with Japanese studios.

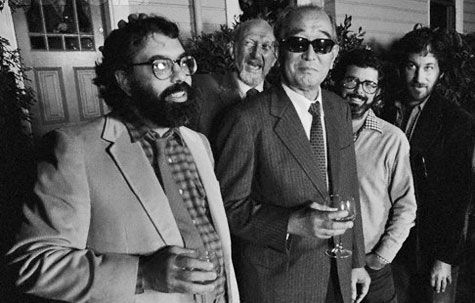

At the end of his rope, he could only make the last five of his films with help from American fans of his work. Maybe you’ve heard of them? George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, and Steven Spielberg came to Kurosawa’s rescue, allowing him to put out projects like Kagemusha (1980) and Ran (1985), which many consider his best work. Dreams was championed by Spielberg, who convinced Warner Bros. to buy the international rights to the finished piece, while Lucas had his special-FX company, ILM, work on the visual effects.

Beyond those summaries, I don’t see the need to delve much further into the vignettes’ intricacies. They speak for themselves on their subject matter and, through independent research and common empathizing, what that would mean to Kurosawa. You, the reader, are not dumb; you can glean their intention without much context. The stories may be blatantly simple, but what interests me more is knowing what they mean to the director himself.

Dreams, if nothing else, is a prime demonstration of the limitless expressive potential a film can hold for a filmmaker. The recreation of his childhood home in “Sunshine Through the Rain,” the intrinsic fear of his mountaineering hobby in “The Blizzard,” and his unbelievable interaction with his favorite artist, Vincent van Gogh, in “Crows”; these are fantasies, deeply-held beliefs, and memories come to life.

It takes nothing short of a cathartic release to realize these sensations for an audience, and we are attracted to that feeling. It’s like when your grandparents tell you their life story, but if they just spoke about the juicy, life-pondering bits. Dreams is those tidbits, sensationalized for the viewing audience but with enough personal attachment to the director to leave you insatiably curious about the actual life of the man who dreamed this up.

This journey into Kurosawa’s subconscious mind is one of the most insightful examinations into the mind of an artist, of a man with life experience he wishes to share. Kurosawa bears all, pouring himself into the canvas that is his script (the first solo screenplay written by Kurosawa in 40 years) and his camera. Reading that critics of the film considered Dreams a self-serving work is disheartening. It’s not self-righteousness or vain moralizing that motivates Dreams, but rather it’s the chance to visualize what perhaps only the mind can create.

It’s not a movie you throw on for the hell of it; it’s something you can only understand if you take the time to look at it intimately. It’s an engagement, a promise to connect with the filmmaker. Other directors do not often extend such an intimate invitation, so take the opportunity where you can.

When one treats film as an art, a realm of expression, it’s inevitable for the filmmaker’s views and homages to their real life to find their way onto the screen. There’s just got to be a method to the introspection that benefits both the creator and viewer, and I think Kurosawa has cracked it. At the very least, I say we let the old man dream.

I found this quote while researching Kurosawa that he supposedly said. I can’t find a citation, but I’ll give the Internet the benefit of the doubt that it’s real. I’ll leave it here with you: “Man is a genius when he is dreaming.” It’s an appropriate attribution, especially in the context of this movie. He needed to bring his dreams to life, just like how van Gogh needed to paint what the world showed him; with time running against him, Kurosawa brought to us the most personal film any director can show a devoted audience.